The Rituals of Dinner

“A meal can be thought of as a ritual and a work of art, with limits laid down, desires aroused and fulfilled, enticements, variety, patterning and plot. As in a work of art, not only the overall form, but also the details matter intensely.”

—Margaret Visser, The Rituals of Dinner

For millennia, humankind has ritualized gathering around the table, be it to celebrate the end of the harvest season, the Harvest Moon, seasonal equinoxes, secular and religious holidays or the advent of a new year. From Nowruz (celebrating the Persian New Year and the arrival of spring), Diwali (the Hindu festival of lights), Día de los Muertos (the Day of the Dead celebrated across Latin America), to the Japanese formal and seasonal kaiseki dinner or the North American celebration of Thanksgiving, each is notable for its particular dishes.

Among the many examples are Sabzi Polo ba Mahi, the traditional Persian dish of aromatic herbed rice with crispy golden fish; also Indian sweetmeats such as halwa, Ladoos and Gulab Jamun; Mexico’s richly sauced moles, pan de muerto and sugar skulls; artfully presented seasonal fish, rice and vegetables; and traditional roast turkey with stuffing. These seasonal dishes are accompanied by traditional rituals such as deep cleaning of one’s home, lighting lanterns, creating beautiful and colorful altars, expressing gratitude.

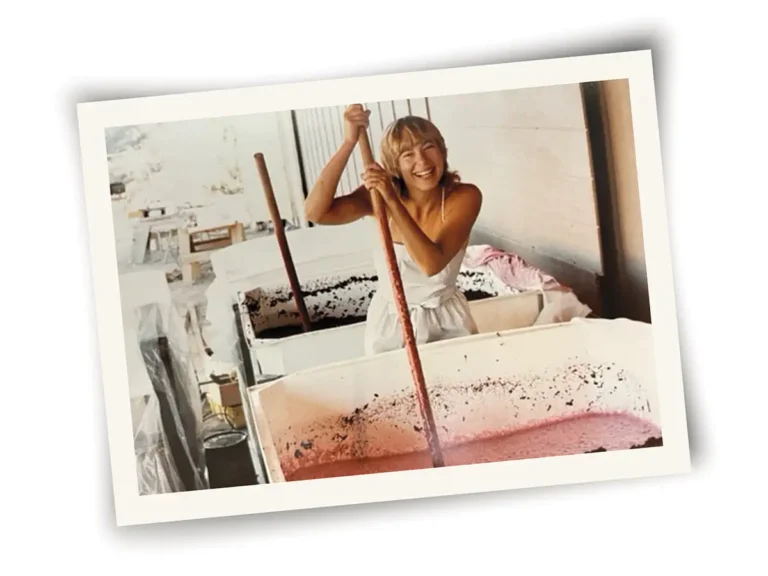

These rituals, and the foods prepared for each festivity, are passed down like a nourishing, continuously seeded ribbon of gustatory pleasures from generation to generation.

There is something comforting in the anticipation and repetition of these dishes. When I asked friends if they ever varied their holiday menus, some said, “Absolutely not, everyone is looking forward to…” and inserted the list of their favorites. For others, it is the act of gathering together that is important, with the meal playing a supporting role, albeit one that conforms in its structure to predetermined familial norms. We are, if anything, creatures of habit!

From medieval feasts around long tables with bread trenchers, to barn raising or harvest picnics, cattle drive barbecues or transhumance festivals or traditional Sunday dinners, these gatherings all have one thing in common: They follow an almost symphonic structure, like a three- or four-part play, orchestrated, like a savory and sweet melody.

Hosts simultaneously play the parts of conductor and composer, arranging tables, compiling guest lists and planning the menu. The dishes served are an edible score, comprising a balance of textures, temperatures, spices, aromas, piquancy and delicacy. Multicourse dinners or multi-dish feasts such as Thanksgiving allow for flourishes and indulgences beyond those served at a regular midweek meal.

My grandmother and mother both perfected the art of entertaining, producing four- or five-course dinner parties with aplomb. As a young child, I longed to imitate them, as these dinners were exciting and theatrical in their gastronomic drama, complete with plumed birds and dishes that were set alight, such as a crêpes Suzette or Christmas pudding. Now I realize that one doesn’t need flaming puddings for a dinner party to be a success—unless, of course, brandy-laced crêpes are your favorite dessert.

As children, we were first taught to set a simple table, then progressed, as we grew older, to more elaborate settings for family festivities and more formal occasions. At my grandparents’ home, this meant tables laid with starched linens, polished silverware, gleaming glasses and cut flowers. I realized that my grandmother literally set the stage by creating an enchanting mise en scène for the meal to come. I have inherited not only some of her fine linens but also the ritualistic manner in which she set a table. I may have modified the menus over time; gone for the most part are the heavy sauces my grandmother cooked, but I do delight in the creation of a beautiful tablescape.

Creating a dinner party menu is akin to writing the score, from a simple rhapsody—a buffet or table set with all the dishes out at once—to a more elaborate composition complete with an overture and a succession of movements: appetizers to whet the palate and tantalize taste buds, such as stuffed dates or savory crostini, followed by a seasonal soup or a delicate salad perhaps; a main course, the highlight of the meal where one might serve a whole roasted fish, a succulent stew or a vegetable tagine; culminating with a grand finale—a dessert, a glazed tart, a cake or luscious mousse.

There is a cadence to the meal, with guests acting partly as audience—observing, tasting and savoring—and partly as orchestra—actively participating in the production of the dinner through conversations, interactions and general bonhomie, conducted by the host in a mouthwatering culinary dance. The simplest rituals set the tone for the occasion, from setting the table and lighting candles to expressing gratitude for those who produced the food, those present and those departed.

Certain meals are inherently ritualistic, following long-prescribed formats with ceremonial foods steeped in symbolic meaning, such as the Jewish Passover seder, the Muslim Iftar during Ramadan, Shabbat dinners and Japanese tea ceremonies.

As I spoke with friends about their families’ dinner rituals, I realized that traditions that arise around the table are not necessarily related to the evening meal, or a religious holy day. One family decided to have their main family meal at breakfast, as their complicated evening schedules—with four children in four different extracurricular activities—precluded their getting together then. Breakfast became a daily, fairly elaborate hearty feast—complete with its own traditions, favorite dishes and specific tasks for all present.

Other families, mine included, always gather in the kitchen before the dinner itself begins. There is camaraderie and a delicious anticipation that arises when surrounded by fragrant aromas. Cooks also want to be part of the action, not squirreled away behind closed doors. This gathering is such a common occurrence now that it has affected kitchen and dining room design. Whereas each room used to be a designated, closed-off space, they are now often inclusive open-plan spaces, reflecting the less-formal nature of mealtimes today.

Recently, as I was preparing the simplest of meals—a light dinner for one—I realized that whether making an elaborate feast for a special occasion with dozens of people or just plating a small salad in a pretty bowl, the rituals and traditions that have anchored our daily lives are as much a part of the dinner as the food itself. Even in turbulent times, there is much to be said for the simple act of gathering together for the rituals of dinner.