The Pleasure of Gatherings

An ode to the love of communing with friends

Alice Waters once wrote, “This is the power of gathering: It inspires us, delightfully, to be more hopeful, more joyful, more thoughtful—in a word, more alive.” This is the motto my family lives by. For as long as I can remember, we have gathered en masse around the table for every meal and every festive occasion. Birthday celebration: dinner party. Seeing friends: dinner party. Family reunion: dinner party. You get the gist. Whether it’s just the family, two or three of us, or the whole tribe—80 or more in France—we sit down and eat together. It has always been thus.

One of my earliest memories is helping my grandmother set the table. She was a perfectionist, and table settings had to be just so. For even the simplest meal, battalions of silverware marched across the pressed tablecloth. At a minimum, each person would use two forks, two knives, a spoon, three plates and two glasses. Different silverware was used for formal dinners where knives, forks and plates multiplied in an orchestrated dance of fine crystal, tinkling bone china and polished utensils. I was captivated by this ritual as it represented the setting of the stage for the meal to come. This was the backdrop upon which she presented all her fragrant, succulent food. Although very young, I wanted a seat at that table; I wanted to belong there.

Young children in the family would usually be fed early and put to bed before the “grown-ups” had dinner. This being France, dinner often started at 8 or 9 o’clock and lasted at least two hours. I longed to sit there, but there was one rule: You would not be excused because you were tired. You were expected to participate in the conversation (or to be silent) until the meal was finished. When I was finally allowed a seat at my grandparents’ table, propped up at the far end (there was a strict seating hierarchy depending on age, gender and birth order), I quickly learned that there were advantages and disadvantages to being granted access to this, to me, hallowed space. The advantage: Adults talked about EVERYTHING—small children notwithstanding. It was fascinating. The disadvantage: 11pm is late for a 6-year-old. I would strain to keep my eyes open and feign not being tired for fear that my now-finally granted privileged access to the big table would be revoked. All this to say that these gatherings held a special meaning for me: I felt as though I had entered a magical, delicious kingdom, and I never wanted to leave.

In London, where we lived for most of the year, my mother carried on the tradition of large dinner parties. These were less-formal affairs; we used less china and silverware, but the structure of the meal was just as elaborate. Three or four courses were de rigueur. We also gathered for even our simplest meals. This was our daily ritual. This was when we discussed the day’s events, school dramas, work issues, politics, weather and food, always food. We often had conversations at lunch, debating what we would make for dinner. There was a conviviality that we all relished.

I recently read an article by Dorie Greenspan discussing meals at home in Paris, in which she wrote: “Dinners at home are not really about the food. They’re about friendship and the conversation that goes on around the table, often late into the night. Yet so much of the talk is about food—the food we’re sharing, the meals we remember, the ones we’ll soon eat, the food we’ve cooked and what we want to cook.”

Her words made me think of Jim Haynes, an iconic American in Paris, who famously opened the doors to his home every Sunday for nearly 40 years, inviting complete strangers to come for dinner. He fed over 100,000 people during that time and delighted in the friendships, love affairs, marriages and babies resulting from his unusual, multicultural gatherings. I love the idea of this melting pot of humanity, coming together to meet others, to commune, to laugh and to discover. He is not the only one focusing on a meal as a catalyst.

Michael Hebb, sometimes regarded as the originator of the modern underground dinner party, once said, “Shelter, in many ways, was provided for us in the natural environment, but the table is a very intentional space created for a communal act of eating together. It’s a pretty wild development in human history.”

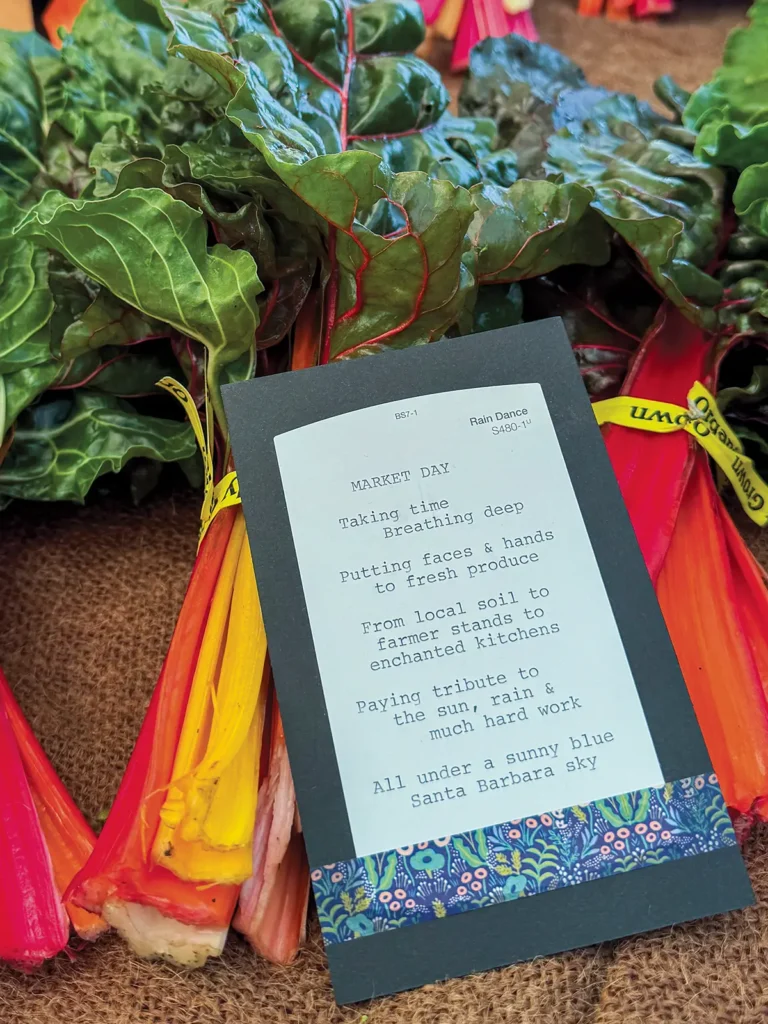

I delight in the idea of an intentional space dedicated to the act of communing together, a space dedicated to our sharing of thoughts as we share nature’s seasonal bounty in the form of the food we make.

As a teenager, I took over some of the cooking at home. We—and by that I mean our entire family—learned to cook for large numbers of people from an early age. From big boisterous winter Sunday lunches designed to satiate the guests after long blustery walks across Hampstead Heath to our annual festive al fresco gathering around the well at my father’s farmhouse in Provence. This was where the garden was transformed into a large lounging lunchtime party, in the style of Manet’s painting Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe (with clothes on, though!). The tiled well served as the large tabletop, and guests served themselves, scattering to eat among the pillows and rugs strewn across the grass, caressed by the summer breeze. These were heady, bucolic times.

My delight in feeding others was not limited to large gatherings and special occasions. During my student days at university in London, dinners consisted of friends crammed around an impossibly small table in the kitchen of my always freezing flat, books temporarily piled on the floor as we delved into dishes designed to thaw us out. We discussed everything from lectures to challenging assignments, whether to go on protest marches and plans for the summer holidays. We laughed a lot.

When you spend hours in a kitchen cooking together, boundaries are broken and friendships forged. Such is the power of breaking bread with friends and strangers alike.

After graduation came work and immigration. I was a transplant to a new country. What better way to get to know people than by inviting them to dinner?

Legions of immigrants have done just that since they set foot in this country; the vast lexicon of worldwide cuisines that form the patchwork quilt of culinary trends across the 50 states is a testament to that. The food people migrate with binds us together, sometimes in poignant and powerful ways. The League of Kitchens based in New York City, for example, is an unusual cooking school whose instructors are a diverse group of women from around the world, each sharing their culinary traditions with students in their homes. Like Jim Haynes in Paris, these gatherings provide a deeper understanding of the world through food. When you spend hours in a kitchen cooking together, boundaries are broken and friendships forged. Such is the power of breaking bread with friends and strangers alike.

This is the premise behind Break Bread, Break Borders, a nonprofit based in Dallas, a “food for good” company where refugee women from war-torn countries are economically empowered by cooking for a living. The idea came about when Jin-Ya Huang, its Taiwanese immigrant founder, in collaboration with local refugee resettlement agencies, hosted a gathering where the community could share a meal and have conversations about refugees, immigrants and the many difficulties they face. The result is an organization centered on the nurturing nature of food for both the provider and the recipient.

Perhaps this is why I have always taught cooking classes structured around a meal rather than specific dishes. As we cook the three courses, we learn not just about the timing of the dishes but also about each other. There is time to listen, talk and enjoy each person’s life experience. There are few settings where this is possible today, as we are bombarded with social media and endless electronic communications.

During the pandemic lockdown, many of us rediscovered the joys of gathering, albeit in different ways. Although we could not eat out or travel, we could still pull up a virtual chair at a dinner table and share a common meal across the ether.

During quarantine, I taught many private classes: retirement celebrations, a father and daughter get-together, business team-building classes, and an extraordinary surprise birthday party linking 18 households from Florida to California. I emailed the recipients the recipes a few days ahead of time. They shopped for the ingredients prior to the class, and then, at the appointed time, we cooked together. We laughed, they told familial stories, we chopped, they asked questions, we whisked vinaigrettes and tasted as we went along.

Despite the physical separation, they were connected through the dishes they prepared together, experienced the same aromas in their kitchens, and tasted the same food. Even separated by thousands of miles, we shared meals with each other, computers propped open on the dinner table to chat and cook with each other.

Now beyond the first wave of Covid, the world is still, it appears, in a state of upheaval. Now, perhaps more than ever, is the time to gather around the table, listen to each other and care for and nurture each other. Such is the power of sharing food. It nourishes us all, body and soul.