Herbaceous

“Pounding fragrant things—particularly garlic, basil, parsley— is a tremendous antidote to depression. But it applies also to juniper berries, coriander seeds and the grilled fruits of the chili pepper. Pounding these things produces an alteration in one’s being—from sighing with fatigue to inhaling with pleasure. The cheering effects of herbs and alliums cannot be too often reiterated.”

—Patience Gray

Have you ever caught the fragrance of basil in the air and thought of pesto, or brushed by lavender and thought of herbes de Provence? Have you noticed how specific aromas conjure up favorite dishes, one’s olfactory memory making a Proustian leap into the past, a remembrance of all things delicious?

Herbs, great mounds of them at the spring farmers markets, have that effect on me. I see tarragon, rub the leaves between my fingers, releasing its anise and peppery scent, and think of the Poulet a l’estragon my grandmother used to make. I see the willowy branches of lemon verbena, swooning slightly at its floral perfume, and think of afternoon tisanes and scented madeleines. I see basil and think of pistou, the rich basil sauce swirled into the vegetable soup of the same name. I am drawn to their fragrance and the promise they hold within their leaves.

Herbs are a culinary paint box, each adding hues and depth to a dish that brightens and invigorates our palates, complementing and intensifying the flavors of a recipe’s main ingredients. Mint added to a bowl of spring peas makes them pop with more flavor. Purée parsley; add some olive oil, capers and anchovies; and you have a piquant salsa verde that will add verve and depth to a platter of roasted vegetables. Anise-scented, feathery dill complements salmon. Finely chop handfuls of parsley and mint, add a little bulgur, and you have the basis for classic tabouleh. Herbs can be transformative.

Cuisines where herbs are more than a garnish are not a modern concept. Dive into the culinary lexicon of most Middle Eastern countries, and you find a rich treasury of dishes that celebrate all things herb. From Egyptian herbalist schools in 1,500 BC to medieval monastery gardens, from a liberal Opposite: Spring Pea and Leek Soup with Pesto and Pea and Mint Hummus. sprinkling of culinary references in Shakespeare’s plays to recipes in some of the earliest known cookbooks, the use of wild and cultivated herbs in medicine and cooking has been documented through millennia.

Herbs proliferate in the oldest known cookery book, De Re Coquinaria dating from the first century AD with recipes such as Artichokes with Hot Herb Dressing, Braised Mushrooms with Coriander, or Baked Trout with Honey Mint Sauce. Seventeen centuries later, in 1699, John Evelyn wrote Acetaria: A Discourse on Sallets, in which he champions the copious use of herbs and greens in healthy cooking. Yet making herbs the focal point of dishes and using them in abundance is a relatively new concept in American cuisine.

Many cookbooks from the 1950s call for the parsimonious use of dried herbs. There are few, if any, fresh herbs in sight except for the odd parsley sprig used as ornamentation rather than for f lavor. The explosion of ethnic foods over the past 15–20 years has changed all of that. The interest in Levantine cooking, fueled in part by the success of books by Yotam Ottolenghi, Claudia Roden, Sabrina Ghayour and Naomi Duguid, has pushed the demand for fresh herbs to all-time highs.

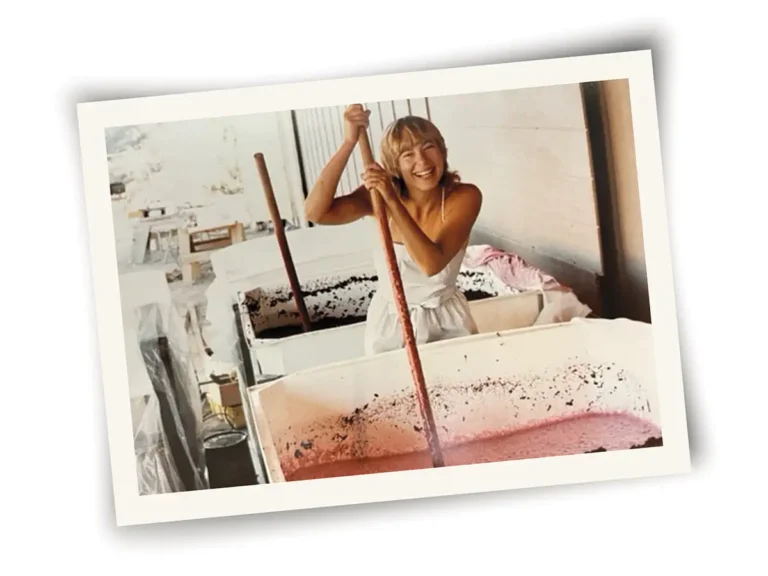

When I first came to California in the mid-’80s, you would be hard pushed to find an array of fresh herbs at the market. Now we find five different kinds of basil, three varieties of thyme, edible flowers and a cornucopia of herbs rarely found outside a keen gardener’s patch until not that long ago.

My love affair with herbs began in my grandmother’s garden, kitchen and at her dining table. She lived high in the French Alps, where the growing season was not long. Her summer garden had chives, tarragon, parsley and chervil. The occasional basil plant sat in her kitchen. On a hook under one of the kitchen cabinets she kept a pair of scissors whose sole purpose was to snip chives. I felt privileged when I was finally old enough to use them.

At her side I learnt to choose vegetables and lettuces with care, to prepare the leaves and make simple fresh salads. Hers were not complicated salades composé, but ones filled with perfect greens and fragrant herbs, dressed with a simple, light vinaigrette. They were crisp and fresh. Ideal palate cleansers served after the main course. She had a deft hand with her cooking, classic cuisine bourgeoise, creating nuanced flavors in her dishes. She used herbs judiciously; finely chopped parsley brought freshness to her Hachis Parmentier (French shepherd’s pie), and fines herbes infused her omelets. These were the steppingstones upon which I built my herbal repertoire.

The more I cooked and explored the cuisines of the Mediterranean basin, the more herbs I used. The more herbs I used, the more I came to appreciate their ability to be the focal point of a dish—their floral, bright notes the arias in an opera of vegetables. I went from teaspoons to tablespoons to handfuls of herbs in recipes.

I have tried them nipped, crushed, striped, rubbed, tossed, mixed and puréed, relishing the fact that these different preparations enhance a different element of each herb. Crushed basil leaves morph into glorious pesto. Thinly sliced into a chiffonade, they provide peppery ribbons of flavor sprinkled over any dish, and small leaves left whole in a salad provide big bursts of flavor, for example.

As a rule of thumb, when cooking with herbs, handle soft herbs, such as basil, dill, cilantro, chervil and marjoram, gently. Their leaves are tender. They damage easily and are better used with little cooking or uncooked when their flavor, color and vibrancy are retained. For example, cooking purple basil will turn the leaves black and mute its heady clovepepper taste. So-called hard herbs, such as rosemary, bay leaves, thyme and oregano with their woody stems, enhance dishes through longer cooking times. Add them to roasts, use them to baste and let their aromas infuse the dish as heat extracts, then releases their oils into the ingredients.

Discover new herbs at the local farmers markets. BD Dautch of Earthtrine Farms has tables filled with an apothecary of aromatic plants. Pick up a bunch of fresh za’atar to roast with Romanesco broccoli, try fresh sorrel leaves in a delicate soup, use lemon verbena to infuse cream to make panna cotta, float chamomile flowers on top of the poached stone fruit. Explore new varieties of your favorite herb, too. Try Thai, lemon and purple basil, for instance, reveling in their unique essence. Above all, have fun and be bold in your use of herbs. Bon appetit!