Butchering Buster

I’m not a chef. The only cooking classes I’ve taken were from Adult Ed, perhaps 15–20 years ago, and all I recall is chopping a lot of onions (too many, actually, and it ruined the dish) and somewhere I might still have the printed recipes. I consider myself a regular person with a particular interest in food. I’m an enthusiast. So there are people out there with far more knowledge, training and experience in food preparation and cookery who can run circles around me.

But that doesn’t make me any less interested in the things that interest me. And I’m interested in knowing more about my food sources. I’m interested in working more with the raw materials and finding fulfillment in putting meals from scratch on my table.

Researching the local pig farm article last spring (Edible Santa Barbara Spring 2015) was hugely inspirational and spanned nearly a year of visiting the farms and restaurants for material. I had the opportunity to observe and photograph Jake Francis’ butchery workshop and to watch Chef Pink break down her first hog in the Bacon & Brine space before the business opened. Part of my drive in doing the article came from wanting to do all this hands-on work myself. Deep down, I wanted my own pig.

In the course of talking to Bruce and Diane Steele at Winfield Farms in Buellton, I learned they had one special Mangalitsa pig that was a genetic dwarf. Her name was Buster, and she was a personal favorite of Bruce’s. The wheels started spinning in my head, and I knew this was a perfect opportunity to make a bid for my own heritage pig that would be a manageable size. They agreed to sell it to me, and last fall Diane announced the time had come.

When Diane contacted me to tell me that Buster would soon be slaughtered, my heart immediately leapt and a wave of guilt came over me about the pig’s death. I wrote Diane, saying I was excited at the news, but also felt sadness. She wrote back this touching note: “I understand the twinge of sadness—we have the same feelings, but we always ensure that our pigs have a good life with lots of food and space to root, and we thank them for their service. These pigs live a far happier existence than commercial hogs that live on a grated floor in a big warehouse and never see the light of day. We passed a few of those on our jaunt to Kansas to pick up Charlie and Petunia … We have a hard time eating pork now, unless it’s ours.”

Ultimately, feeling this discomfort should be a good thing. It means I acknowledge that a creature’s life was taken. I hope I never lose that feeling and become disconnected from the process.

By early November, Buster came to me as two sides of USDA stamped and approved pork, about 150 pounds in total. Her dwarfism meant that she was about 100 pounds less than other Mangalitsas her age, yet with all the anatomy of a regular pig and a full-sized head. Immediately half went to a friend I’d split the cost with, and I drove away from Buellton with a car trunk full of pig. Even 75 pounds of pork is a formidable amount for one person, much less a five-foot-two woman, and I’d decided that this Buster project would be mine alone from start to finish. I questioned that decision before Buster even got in my house—trying to get the carcass out of my car. Thankfully, my side came in three main pieces: the head and offal, the shoulder primal, and everything else. It was the “everything else” portion that was the problem—it was a single piece weighing over 50 pounds. I decided it was late, and moderately cold, and it could live a night in my car under ice and be dealt with in the morning.

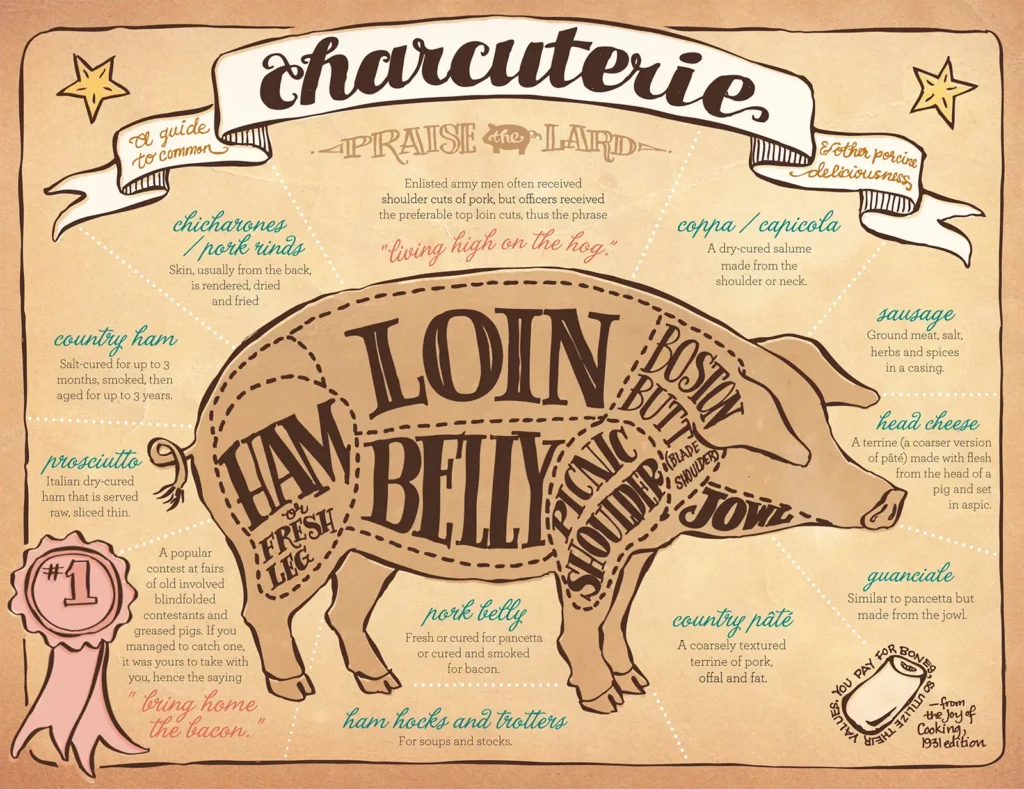

Watching Chef Pink and Jake Francis butcher a pig was immensely useful, but it had happened months earlier. I needed butchery resources at immediate hand. Thankfully, I found a series of Internet videos produced by Food Farmer Earth. These instructional videos were led by a petite woman from the Portland Meat Collective who broke down a side into primals, and then produced a full range of cuts that would result in a variety of fresh meat for grilling and roasts, cuts for brined and smoked ham, cured bacon, sausage, and dry-cured charcuterie. I didn’t want to take the easy route on this pig—this was an opportunity to get experience in a wide array of meat processing and I was going to make a spreadsheet of it all.

The Food Farmer Earth’s series takes nearly an hour to watch, but is thorough, educational and since the woman had a similar stature to me, her description of measurements matched mine. “…I have skinny fingers, so I go about three fingers off the aitch bone… if you have larger fingers, go about two fingers…”

In the morning I returned to the car and faced the meat. It was in a large plastic tub that was too heavy to pull from the vehicle, and the pig too heavy to lift with my arms over the top of the tub. I tugged at the leg in frustration until I was slowly heaving the carcass across my back and eventually I was carrying the full piece, hunched over. There, I did it. I crawled through my front door with a piece of pork half my weight on my back, wailing something about what have I gotten myself into.

Top row, left to right: Buster was a genetic dwarf with a full-sized head; the ham primal cut is the back leg, which can be smoked for a traditional ham or dry cured into prosciutto; Buster’s coppa, a bundle of muscle at the top of her shoulder in the Boston butt, is prepared for a dry cure for Italian capicola. Middle row, left and right: Single-origin sausage, made from Buster’s shoulder meat and small intestines. Center: Buster’s belly, cured for pancetta and smoked into sweet bacon. Bottom row, left to right: Fresh chops cut from the bone-in loin; Buster’s ham leg, covered in salt and hung for a year to cure into prosciutto; a fresh roast with a generous fat layer for crackling comes from the picnic ham in Buster’s shoulder. Photos: Rosminah Brown

The next obstacle was storage space. No household fridge can hold a 50-pound solid side of pork as well as the supplies necessary to run that household. And my other major limitation was the working space and chopping board in a small cottage. All I had was a little kitchen island approximately two square feet. The first steps, for logistical reasons and for food safety, was to get these large pieces cut down to workable, and storable, size. For the next few days I rose at the crack of dawn, sometimes earlier, and would watch the videos of this woman butchering a pig, then put on my apron and get to work. Like Chef Pink once talked me through—the first thing to do with your pig before cutting is examine it. Feel out the muscles and fat, run your fingers over its contours and find its seams.

I watched each video at least three times. Once in the morning to go over what parts I’d be working on, a second time just before I’d set to work on a specific part and the third viewing would be while I was butchering, with constant pausing while I matched the cutting to the video.

This was my life, from sunrise until late at night. A professional butcher can break down and process a pig in just a couple hours. It took me over a week. But I was precise and made no effort to work in a hurry. If I felt I had worked on one piece too long, I’d stick it in the fridge and work on another cut.

One thing about my pig, my Buster, that was remarkably different from all the pork I’d ever bought from the store was how it smelled. It smelled beautiful. Does that even make sense? Raw meat from the store always smelled like … meat. Kind of bloody and metallic and harsh. Like something you know you had to cook before you could eat it. This local Mangalitsa smelled soft, clean and fresh, almost floral. It was a true pleasure to stick my face right up to it and inhale deeply. This was how good meat should smell. Just like fresh fish shouldn’t smell fishy. In the whole week I worked on the raw Buster, the meat always smelled wonderfully fresh.

My knife work was so slow and precise that there was very little waste. I occasionally had to intentionally slice off little pieces in order to have an excuse to taste test. The first slice of shoulder, quick-cooked on a hot grill with a pinch of salt and pepper, was all that was needed to convince me that good fresh pork was a thing of wonder. It was juicy, sweet and tender.

A few friends came over during this process. Not to help me with the work, as I had set a strict goal to do this solo, but for company, chatter and some mental support. And I got to feed them pieces of whatever I was working on. It was a pleasure to feed them. It was a pleasure to take breaks, too. When I really needed to move away from the meat, I would wash up and sit down at the laptop to write up my notes and research the next steps. Or I’d go for a two or three mile run to clear my head and stretch my legs.

The cutting turned out to be just a fraction of the work involved with Buster. Next was making good things with all the cuts of pork. I did not make this easy for myself. Remember, I had a spreadsheet. I was going to do Buster proud.

I cut pork chops and porterhouse chops from the loin, separated the belly and cured half for sweet smoked bacon, I rolled roasts from the picnic hams and started dry cures for the coppa in the shoulder and set the whole leg into several pounds of salt to become a year-long dry cured leg much like prosciutto. Bones simmered into stock and the trotter added gelatin to the stock.

The shank was brined in a friend’s homemade ale and smoked alongside the bacon, and would be used in a fantastic smoky and meaty pot of Shackamaxon beans that I’d bought from Roots Farm at the Saturday farmers market. The intestines alone became a day-long project to clean and prepare as sausage casings and I used these to stuff with Buster’s shoulder meat into two kinds of sausage. Imagine that, a fully single-origin sausage! The rest of the casings were set to store in salt for future sausages.

Buster’s head, while just a fraction of the overall hang weight, turned out to have so many individual projects, it took up the most amount of time to process. The jowls became smoked bacon and guanciale, the cheeks removed and proved ideal for rich braises. The ears and tongue could have become their own dishes, but I ended up putting all of them into a melty and meaty amalgamation aptly called head cheese.

Most of the fresh cuts of meat and sausages went straight into vacuum-sealed bags and into the freezer. Also packaged up were portions of fat and skin, to be used for future chicharrones, Chinese soup dumplings (xiao long bao), sausages and lardo.

Over five pounds of kosher salt disappeared into all the brines and cures for the longer-term projects. The cured coppa was ready to eat just a couple months later and sliced into fine, buttery and savory capicola that I wrapped around figs, ate with melon or drizzled with olive oil and draped over warm crusty bread. And to think that I used to lump the coppa into a random pile of shoulder meat that would be ground into sausage. I will never do that again now that I’ve made capicola that’s fed so many friends over several dozen meals.

Honestly, the hardest part of the whole project was the daily shuffle and dancing between multiple home-size refrigerators and a friend’s chest freezer: always having to think a few steps ahead on what I’d be working on next, moving things between fridges and homes, getting cuts bagged and sealed and moved offsite to the chest freezer without inconveniencing others.

I tried a lot of new things that year, which included free diving for abalone, running my first half marathon and even an ultra-marathon, all significant events. But Buster was truly the highlight of the year. To be able to get my hands on a local heritage pig, challenge myself to produce a range of edible products from it, and get one step closer to walking the walk of truly knowing and respecting my food sources, it means a lot. I’m just a regular person who doesn’t want to be disconnected. But I really could use a bigger fridge.

Recipes

The benefit of having a whole pig to work with is the wide range of dishes that can be made, from fresh chops to head cheese, charcuterie and lard. Buster the Mangalitsa provided so many preparations, it had to be managed on a spreadsheet—starting at the primals, and accounting for parts down to the intestines (that made sausage casings) and tail (braised, then roasted).