Belonging… and a Bag of Lentils

“The dynamism of any diverse community depends not only on the diversity itself but on promoting a sense of belonging among hose who formerly would have been considered and felt themselves outsiders.”

—Sonia Sotomayor, associate justice, U.S. Supreme Court

I stood in the farmers market early one morning, running my hand through a container of lentils, discussing their merits with Jacob Grant, owner of Roots Organic Farm. These weren’t just any lentils; these were tiny, dark green French lentils that I had coveted since I was a small child. I was transfixed and transported. Is it possible, I thought, that just finding these beautiful lentils in my local market could make me feel at home? More on these lentils in a moment.

I pondered the question of what feels like home. What makes one feel as though one belongs somewhere? Is it proximity to one’s family? Is it because we feel free to be ourselves? Because we feel safe? Can food make us feel as though we belong somewhere? Or is it because we feel comfortable wherever we are by cooking the food that we are familiar with?

I realize now that I have never really felt as though I belonged 100% to any one place. I grew up in London in a family that straddled the English Channel, one foot firmly planted on either side, adopting each culture’s food, language and idiosyncrasies as situations dictated. As a result, I sometimes felt very English in France and vice-versa.

Our family patois reflected the hybrid nature of my upbringing, dipping in and out of whichever language provided the mot juste. We made Tarte a l’onion in London and apple crumble in Provence, a mashup of tastes, recipes and traditions that represented everything we were (and are) as a family.

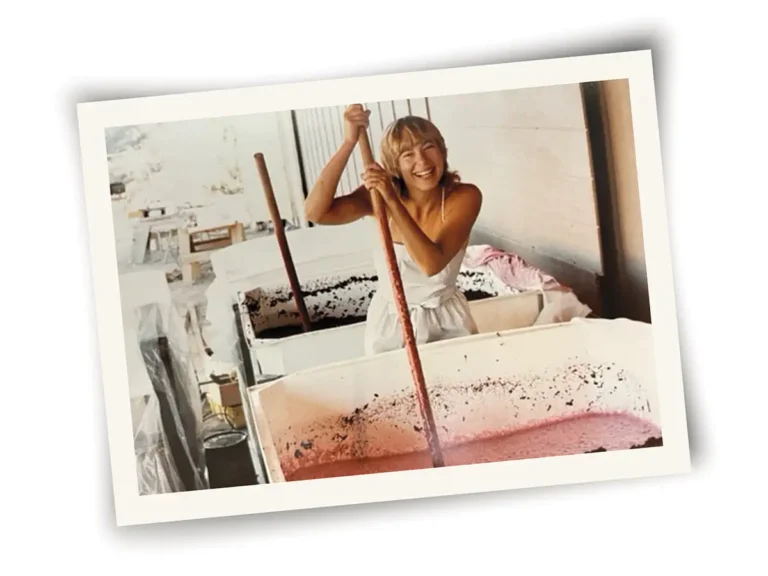

Like many people in California, I am an immigrant—part of the diaspora of myriad nationalities who have migrated to this sunny climate—and like most transplants, I brought my food culture with me when I arrived here nearly four decades ago.

When I moved from one sprawling metropolis, London, to another, Los Angeles, in the mid-’80s, it was something of a culture shock. This was the time of frothy daiquiris, wedge salads with green goddess dressing, and smoked salmon on pizza a la Spago, in a city where people ran around all day in workout clothes with big bleached froofy hair, when people wore sneakers with their big shoulder-padded suits, the bank manager called me by my first name the first time I met him, and guests always asked me to put vinaigrette on the side whenever they came over for dinner.

I didn’t quite know what to make of it. I had laughed at the English American dictionary a good friend gave to me before I left London. “What do I need that for?” I said. “We speak the same language.” Well, yes and no. George Bernard Shaw once said, “We are two countries separated by a common language.” Initially, I was trying to figure out how I would fit in, as I often felt I didn’t speak the same language at all.

I worked for nearly 14 years in the concrete vastness of Los Angeles, hanging out with groups of fellow expats, a motley crew of transplanted Brits and French men and women. As immigrants do in new countries, we found each other, creating recognizable communities in foreign lands. All immigrants seek familiarity abroad, even when they speak the same language as their hosts. I searched for French bakeries, restaurants and farmers markets to feel more at home.

I found integration a challenge. We had different customs and traditions. I missed France and England, but I simultaneously appreciated the incredible opportunities I had on the work front that would not have been available to me had I stayed in England. We worked and interacted with thousands of people, but did we really fit in?

This disjuncture was all the more evident at Thanksgiving, the quintessential American holiday. Everyone we knew went home or celebrated with their families. In the early years, our motley crew looked at each other and said, “We’ll create our own traditions. What could be better than a holiday centered on gathering people around the table?” Every year we cooked up a storm and ended up with our slightly quirky, transatlantic version, complete with Tarte aux Pommes instead of apple pie.

The menu, I soon realized, was not the most crucial thing (some may disagree with that), but rather, it was the gathering together of friends and family. We felt a sense of community as we set the table, prepared the food and ate together, but was this genuinely belonging?

One weekend, a chance visit took my family 90 miles up the coast, giving me a sense of déjà vu. The Mediterranean styled, red-tile-roofed city of Santa Barbara sits nestled between the ocean and the mountains. I was immediately struck by the similarity with coastal towns that dot the Cote d’Azur, the hills to their backs, with houses running down to lap the water’s edge. I had spent much of my childhood and adolescence in such towns.

This place felt, well, familiar. The friend in whose cottage we were staying mentioned a farmers market. We went. As I strolled through the aisles of exquisite produce, I could see the chaparral-covered mountains in the distance. The similarities were uncanny and comforting. Both places have similar climates and architecture, with vineyards in the backcountry. My life in Provence often revolved around our local village’s Tuesday and Saturday markets. Even the market schedule here was the same. As soon as the opportunity presented itself, we decamped the 90 miles up the coast.

Children are often the conduit into a local community. Mine were just that. As I immersed myself in school runs, the PTA and starting a new business, I felt myself planting roots. Each town or city I’ve lived in has its rhythm, and its citizens tune in to its cycles to a greater or lesser degree.

This town felt natural to me, as though I had pulled on a comfy sweater. It started to feel like home. As the years passed, I realized that one’s true sense of being is not just dependent on a physical place but very much on those who populate it, on the community you support, and that, in turn, supports you.

Which leads back to those beautiful soft lentils. As I held them in my hand, I felt a tangible link to my other homeland, realizing that I now had feet straddling another body of water: one foot in Provence and another in the American Rivera. I felt a kinship with those who tend the land and nourish us on both sides of the Atlantic, and perhaps that is why it’s not at all a coincidence that the experience I enjoy the most is gathering friends around the table, wherever that table may be. It is a chance to share our lives, to laugh, to cry, sometimes both simultaneously, to reflect, and in sharing the food we have prepared together, we share ourselves. This is belonging.