The Pursuit of an Ideal: The Pioneering Spirit that Defined the Sta. Rita Hills

The story of the creation of the Sta. Rita Hills AVA is one of conviction, determination and faith intimately woven into the character of vintner Richard Sanford. Anyone in the Santa Ynez Valley wine world will tell you that one cannot be referenced without the other.

I have been waiting for this moment since last year, when I began this journey of writing on the origins of Santa Barbara County’s American Viticultural Areas (AVAs). It was a 1976 vintage Sanford & Benedict Cabernet Sauvignon from the “Coastal Hills of the Santa Ynez Valley in Santa Barbara County” that ignited my curiosity to explore this road.

I was speechless when tasting this wine, mesmerized by the label and the integrity of the wine. I had heard the stories that Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Chardonnay and Riesling were among the fashionable varietals originally planted at the vineyard in 1971. Today only the Chardonnay remains—the others are long gone, as is the Sanford & Benedict brand. Like all history, memories shift through time and truth becomes malleable. Yet here was undeniable proof in my wine glass that the past was alive and well and those accountable for it had stories to tell.

What is now the Sta. Rita Hills was once called the Western Santa Ynez Valley. When Richard Sanford first came prospecting for vineyard property in 1969, many local farmers considered this land too cold to plant grapes. While agriculture was diverse in the area at that time with ranching and row crops, grapes were thought to be better suited for warmer eastern areas. Local farmers, of course, thought he was nuts.

“There was a vineyard in the area,” laughs Sanford, recounting those early days. We are sitting in his current Alma Rosa Winery office on a cool, foggy September harvest morning in 2016. Various maps decorate the walls and viticultural books line the shelves.

“It was the Nielson Vineyard planted in 1964 on the Tepesquet Mesa in the Santa Maria Valley.” Interest was building during this time for grape growing with tax incentives and the allure of premium pricing for product on the temperate coastal zone. “San Joaquin Valley grapes were $52 a ton for Thompson Seedless and out here it was $152 a ton for these fancy coastal grapes,” Sanford said.

It was during this time that other pioneering folks were also scouting land to set down roots. Within a few years, famed vineyards such as Rancho Sisquoc, Bien Nacido, Zaca Mesa and Firestone would be planted. But at this moment in 1969 it was just Sanford—a Vietnam naval veteran looking to find a renewed space in the world after feeling rejected by the culture that drafted him—driving around Santa Barbara county in his 1959 Mercedes looking for peace.

“You are a product of the time in which you are living,” Sanford said. “The defining circumstance in my coming of age was the Vietnam War and everything that came with it. I mean, to be spit on after coming back from a war… it was very confusing for young people.”

Sanford is an even-toned, steady man. After more than 45 years in the wine business, he speaks reflectively as someone who has seen it all, with a resolute tone of someone who has earned it. He began telling me that his strategy for coping with this rejection was to rebuff the culture that sent him to war. He needed to be involved in something more grounding and connected to the earth. Agriculture became his solace.

During this turbulent time he harkened back to a memory he describes as his threshold wine experience. His shipmate named Scott Wine, of all things, introduced him to a Pinot Noir from Volnay in the Burgundy region of France that would change his life. “I was thinking about that Volnay and the structure of the velvet,” he said. “Why couldn’t I be involved in creating a beverage like that?”

Identifying Place

Before the war, Sanford graduated from UC Berkeley with a degree in geography and he used his education to analyze soil and climate data of Burgundy, France. His goal was to identify an area closer to home that best matched its characteristics. It is now legend that Sanford drove up and down Highway 246 from Santa Ynez to Lompoc with a thermometer taped to his car. He discovered that the temperature cooled by one degree for each mile he drove west. His original hope was to plant a vineyard near Lake Cachuma, though he soon recognized it was too warm for Pinot Noir. “You have to be where the grapes want to be,” he said. That is when he found the stretch of land conducive to his goals.

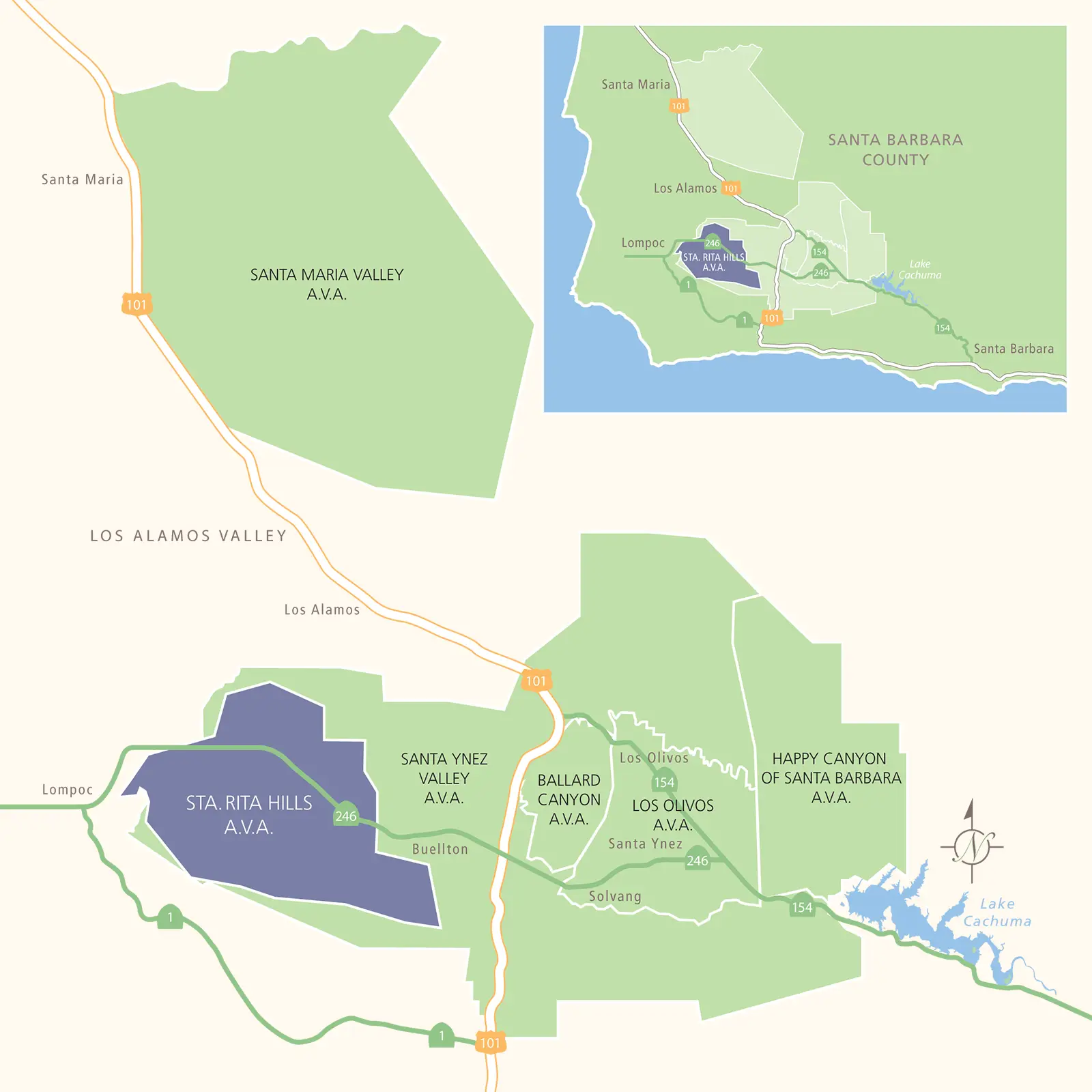

The Santa Rita Hills is an oval-shaped formation in the center of the Santa Rita valley. The transverse mountain range that cradles the area is its essential geologic characteristic, with the Purisima Hills to the north and the Santa Rosa Hills to the south.

In a transverse system, the range runs east and west, unlike more standard north-south configurations. The proximity to the ocean—about 10 miles—creates a cooling maritime influence that is funneled in with morning fog and intense wind. Coupled with poor marine soils deposited from tectonic shifts millions of years ago, these variables create complicated growing conditions for any crop. Those farmers questioning Sanford’s intentions were not wrong, they simply did not understand that these characteristics created a favorable environment for producing premium cool-climate grapes.

It didn’t take long before others took notice, after Sanford and his then-partner Michael Benedict planted the abandoned bean farm that would become Sanford & Benedict with vine cuttings from the lone Nielson Vineyard in Santa Maria. Pinot Noir was planted a few years later.

In the span of just over 10 years Lafond, Sweeney Canyon, Huber and Babcock vineyards were also planted. By 1984 when Bryan Babcock started making wine on Highway 246 with his father, Los Angeles was a major market for wines coming from the newly created Santa Ynez Valley AVA.

“The first real heads turning for wines from the Western Santa Ynez Valley were with the Pinot Noirs that Richard and Michael made in the late 1970s,” said Bryan Babcock of Babcock Vineyards.

“In an environment where the wine media concluded that you can’t make a Burgundy-style wine in the New World because the grape is too fickle, all of a sudden Sanford & Benedict is producing these dark, rich, expressive Pinot Noirs.” Babcock soon planted Pinot Noir at his ranch and in the coming years more growth followed.

Chardonnay and Pinot Noir were recognized as the primary grapes to plant and new vineyards such as Cargassachi, Mt. Carmel, Clos Pepe, Fess Parker, Fiddlestix, Melville, Fe Ciega and Sea Smoke were listening. The energy was palpable. “The cat was out of the bag,” said Babcock.

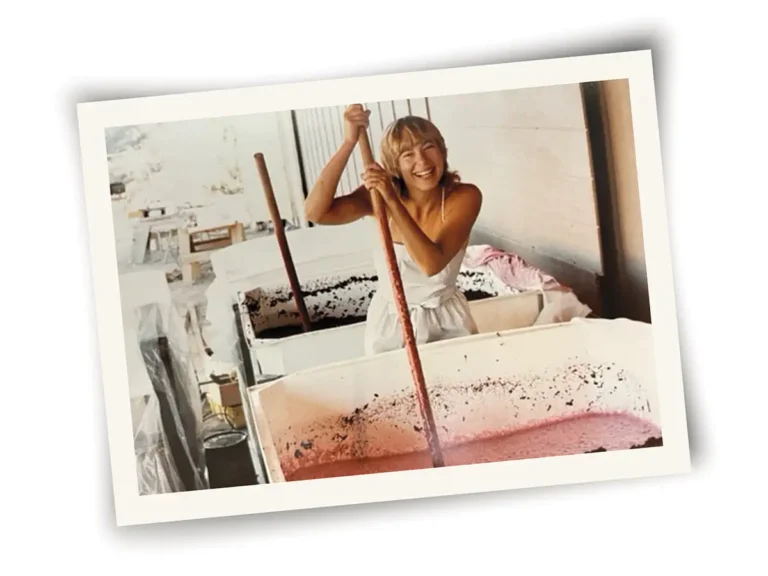

One major issue was conflicting these early adopters, particularly Richard Sanford, who by the mid 1990s was producing 50,000 cases of wine sold all over the world under the Sanford label with winemaker Bruno D’Alfonso.

“The perception in the wine media was that the cool Santa Maria Valley was the place for Pinot Noir, and the warm Santa Ynez Valley was the place for Cabernet Sauvignon,” said Sanford, who years earlier had grafted over his original plantings. “I wasn’t happy about that.”

When the Santa Ynez Valley AVA was approved in 1984, it was an all-inclusive effort to encompass the dozen or so vineyards south of the Santa Maria Valley. Now with 500 acres under vine in the western Santa Ynez Valley producing drastically different wines from the east, winemakers wanted acknowledgment for their distinct efforts.

The Santa Rita Hills Winegrowers Alliance was born with Sanford as chairman, Dan Gainey of Gainey Vineyards as treasurer, newcomer Wes Hagen of Clos Pepe Vineyards as secretary and Bryan Babcock as mapmaker. The goal was to define the appellation of the Sta. Rita Hills AVA.

The Beginning

For years Wes Hagen was the unofficial spokesperson for the Sta. Rita Hills. First, because his energy is unstoppable, and second, he gives 100% to everything he does. On this harvest morning I am sitting across from him at Pappy’s Restaurant in Santa Maria near his current job as winemaker for J. Wilkes, asking him to recall the early association days 20 years before.

In 1996 he was a cellar hand learning the craft with Bryan Babcock. One day, after a wine writer had visited from Napa, Bryan began to get agitated.

“This guy drove down for two hours to write about some crazy guys making Pinot Noir on the west side and he was going to drive home and define who we were without us having any control over it,” Hagen said. “Babcock was in the mood of self-determination overlooking the valley and he said, ‘This is the Santa Rita Hills.'” That was the first time Hagen had ever heard that term used.

The group included about 30 winegrowers and winemakers in the area—”renegades,” as Sanford recalled—who met in his map room looking for qualitative markers to define their borders. They studied climate data, analyzed watersheds, shared their experiences throughout the area, visited vineyards and trekked (oftentimes trespassed) on properties from ridgeline to ridgeline identifying the markers that created their unique microclimate.

There are photos of Sanford, Rick Longoria and others walking with geologist Thomas Dibblee, who lived in Santa Barbara and created the indispensable Dibblee Maps that documented soil data, among other things, along the hillsides in the Santa Rita Hills.

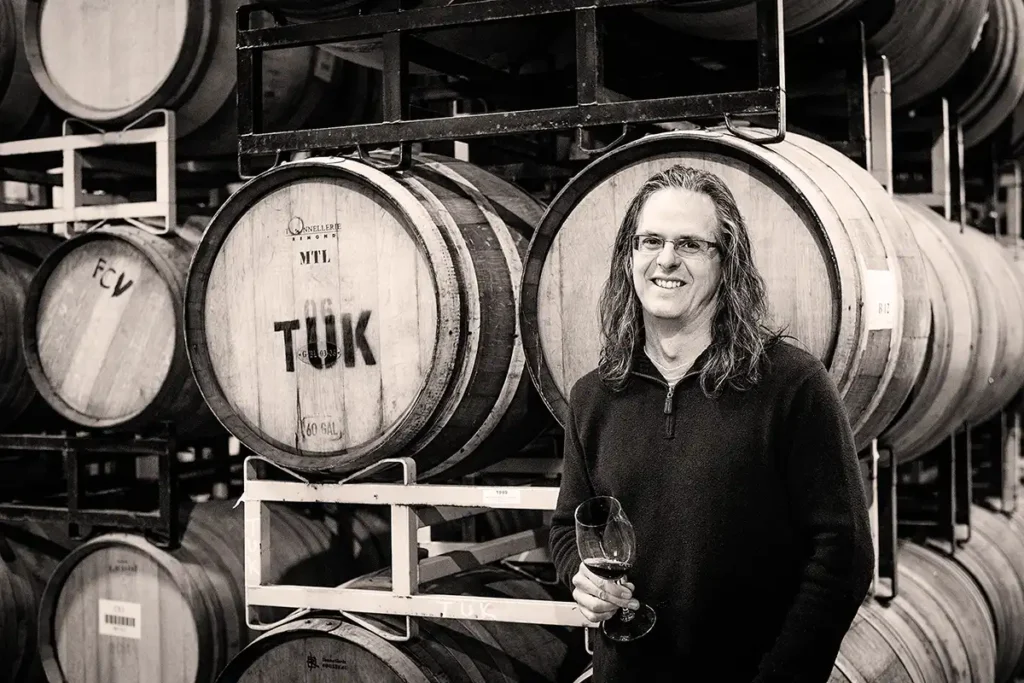

“We were all there because of Richard,” said Greg Brewer of Brewer-Clifton, started in 1996 with Steve Clifton, focusing exclusively on Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. “It was his world, his spot. He was the elder statesman.”

Brewer was the one who gave me the Sanford and Dibblee photos. If Hagen was the unofficial spokesperson for years, Brewer is the torchbearer who has traveled the world from Sweden to Japan and all across the United States spreading the gospel of the Sta. Rita Hills. “I have dedicated my entire career to an eight-mile stretch of land. This is my hometown.”

The goal of the Sta. Rita Hills appellation was to be a cohesive, structured and targeted area based on climate and geology. “The reasoning behind the expansiveness of the Santa Ynez Valley was appropriate back then,” Brewer said. “With the Sta. Rita Hills we wanted to do it right to create a meaningful, dedicated and specific AVA with a strong influence on our two most important grapes: Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. We were trying to get away from the broader Santa Ynez Valley message that we can do it all. Through this process we became an aligned force of people important to the success of the Sta. Rita Hills.”

After a year of meetings and research, Hagen was chosen to write the AVA application, which he calls his watershed moment. When the petition was submitted in 1997 there were nine wineries in Santa Rita Hills. When the petition was approved in 2001 there were 20 wineries. Today there are 52 members of the Sta. Rita Hills Wine Alliance, with 2,700 acres planted primarily to Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. This seems to be only the beginning.

“The motivation behind the appellation was very sincere,” said Brewer. “The wines are carnal and very raw. There was no political weirdness or strained association for economic play. It was very grassroots, humble and honest and I think the wines continue to be that, too.”

A New Era

Once the Santa Rita Hills AVA was approved, the Santa Rita Winery in Chile immediately contested it. As a 120-year-old, international winery producing 3 million cases annually, it felt the handful of wineries in the Santa Rita Hills would dampen its name recognition. As a testament to his diplomacy, Sanford met personally with the winery group in Chile and drew up an agreement without lawyers where the California AVA would abbreviate its name in writing to the Sta. Rita Hills. This allowed the Chilean winery to keep its integrity while upholding the approval by the United States government.

Today, the Sta. Rita Hills is considered the most successful AVA in Santa Barbara County based on name recognition and cohesive consumer message.

“In terms of marketing dollars and reputation, we are the best guerilla AVA ever created,” said Hagen. “We make wine that is absolutely unique. We make wine that king-maker critics love because we can make the biggest, darkest, richest Pinots on the planet if we want to. We can also make the most mineralladen, elegant, acid-driven wines. We have built-in quality and support by first generations making kick-ass wines.”

It is also one of the most valuable AVAs for Pinot Noir and Chardonnay in the state, sought after by winemakers throughout California looking to create complex wines that garner premium pricing.

“We have the ability to make this incredible spectrum of wines,” said Mike Testa of Coastal Vineyard Care, while standing at the John Sebastiano Vineyard on the east end of the Sta. Rita Hills AVA. “You can never make a wine that is this concentrated from any other part of the state. Most of the Pinot Noir in California is grown between King City and Soledad with huge clusters and huge berries. Even in extremely ripe conditions they are still not producing a wine that delivers the concentration that we deliver from the Sta. Rita Hills.”

Testa said he has been lucky in his career to farm in every major growing region in California and the ability of the Sta. Rita Hills to produce super-low-yielding, small-berried clusters of Pinot Noir in some of the most extreme growing conditions is unparalleled in the state.

“Because of the soil, wind and drought conditions, there isn’t a point in the year when the vines are not stressed out,” said Testa. “The vine knows that and it is producing a small cluster, with small berries that it knows it is going to ripen. We know we are going to turn that into wine with great extraction. Within this small stretch of space you have this incredible growing climate that suits Pinot Noir and also keeps great acidity, which is what make us different at any level of ripeness.”

For Brewer, access to grapes in the Sta. Rita Hills was hard to come by in the early years of Brewer-Clifton. Fruit was simply not available. He remembers writing handwritten letters to vineyard owners, asking for grapes. When a contract did come through, it wasn’t always a stable agreement for the following year.

“Fruit was definitely something that was hard-earned back then,” Brewer said. He and Clifton eventually decided to lease property and plant their own vineyards in the mid 2000s to secure their sourcing for their future.

Contrast that to current day, when a healthy portion of Sta. Rita Hills grapes are trucked out of county, primarily to larger Napa and Sonoma wineries who don’t want to be left out of this growing system. While local consumption has stayed the same in recent years, outside demand keeps climbing.

“Some of the best parcels of land in the Sta. Rita Hills haven’t even been planted yet,” said Testa. “We are focusing the majority of our efforts in this area.”

Walking with Brewer in his Machado Vineyard parcel after harvest, with fruitless vines and browning leaves, I ask why the Sta. Rita Hills is so special to him beyond the transverse mountain range and the windswept landscape that is unique to everyone sourcing fruit in the area.

He smiles at me in a way to say I can’t truly understand if I have to ask.

“It is all of it,” he said. “It is the huge answer to that terroir question. It is the valley, the wind, the fog, the soil. It is Richard in ’71. It is us in ’96. It is Bryan and the nuns at Mt. Carmel. It is the history of it. How we mapped it in a couple of 4Runners buzzing around looking at ridgelines. It is all nourishing and enriching to this community. There is so much more to it than circumstance.”