Salt of the Sea

[Photography by Fran Collin]

Growing up near the beach in Southern California, I’ve swallowed my share of ocean water while playing in the waves and know first-hand that it’s pretty salty. But I’d never considered looking beyond the grocery or specialty market shelves for salt until a discussion during our Eat Local Challenge made me wonder if local sea water might yield edible salt.

Steve Escobar, a local crab, lobster and spot prawn fisherman, is always on the lookout for new culinary treasures hidden beneath the surface of the ocean. “I own a live fish market in Newport Beach called the Dory Fleet. My customers always ask me how to cook stuff,” he says. He often sells his customers Macrocystis kelp, a local seaweed, to steam with their lobsters. “It makes a fragrant poaching liquid and tons and tons of it comes up in my traps.

Steve’s Portuguese heritage has given him an appreciation for often-overlooked items like shield and rock limpets, which are commonly served at Portuguese festas. He is currently looking for new uses for the fresh kombu seaweed—used in Japanese dashi—found in deep water. Between fishing trips, he attends culinary classes at Santa Barbara City College to get new food ideas and to polish up his cooking skills.

I first met Steve aboard his boat, the Ocean Pearl, at a Santa Barbara Food and Farm Adventures Meetup. He’d offered to take us out on the ocean to gather crabs from his traps and show us what freshly caught crabs taste like. Armed with homemade wooden mallets, we cracked our way through one delicious quickly boiled crab after another, eating every sweetly flavored tidbit we could capture—no lemon butter needed.

A few months later I ran into Steve at the Sol Food Festival. His eyes lit up when I told him about my sea salt interest. We were both curious how much salt the ocean water would yield. He offered to take me out on his fishing boat to get some clean, blue water. This deeper water is less likely to have concentrated run-off pollution.

By the time I contacted him to set up a water-collecting trip, he’d already done some research of his own and was considering the possibility of a larger-scale production. Steve studied Agricultural Business at Cal Poly, but his entrepreneurial spirit took hold long before that. Steve says, “When I [was] just a little tyke, about 8 or 9, I started selling eggs door-to-door from a little wagon. My friend’s parents had a big chicken ranch. I’d buy eggs from their ranch and go sell them.”

In high school Steve set up a car stereo shop with his brother Mike. “When I went up to college Mike kept the stereo shop going.” During summer break, Steve decided to grow corn with a buddy. He says, “I’d get up at 4am, pick up a couple of truckloads, park on a corner, and my niece would sell 10 ears for $1 while I went off to my other job at the stereo store.”

When he finished college, he took a job in sales for a computer company, opened an office for them in Los Angeles and he eventually moved on to work at Lockheed and then Tektronix.

On weekends and vacations, he’d go diving and fishing—fishing was in his blood. He’d grown up on stories of fishermen relatives in the Azores. He says, “I loved seafood and the ocean. My grandmother would take us to Santa Cruz when we were kids. They had a little boat there so we’d fish for rock cod and crabs. I just got hooked.”

“One day while flying back from a business meeting,” he says, “I just decided to quit and fish full time. A friend had taught me how to catch lobster, and I thought maybe I could make a go of it.” He purchased the Newport Beach fish market in 1997. In 2001, he got the opportunity to fish for crab and moved to Santa Barbara in 2005.

Collecting Ocean Water

It was clear to me that I’d chosen the right guy for the sea salt adventure. As we headed out for the blue water, I ducked into the cabin to warm up. The clouds on the horizon were threatening rain and the seagulls were heading for the parking lot. On the wall, next to the fishing poles was a net storage pouch normally used for fishing gear. Steve’s was filled to bulging with jars of herbs and spices. If anyone else could get excited about homemade sea salt, it would be Steve.

I went home with five gallons of ocean water. I’d previously tried beach water that had to be filtered multiple times until it looked clear enough for me to risk tasting the salt. A word of warning here: A Santa Barbara 2001–2006 Water Quality Monitoring Program Report found trace metals arsenic, cadmium, copper, chromium, mercury, nickel, silver, zinc and lead in the storm runoff water tested during that period. While bacteria and viruses probably won’t survive the boiling and the concentrated salinity, metals and possible toxins could remain in the extracted salt. Only a detailed analysis of the salt can guarantee its safety.

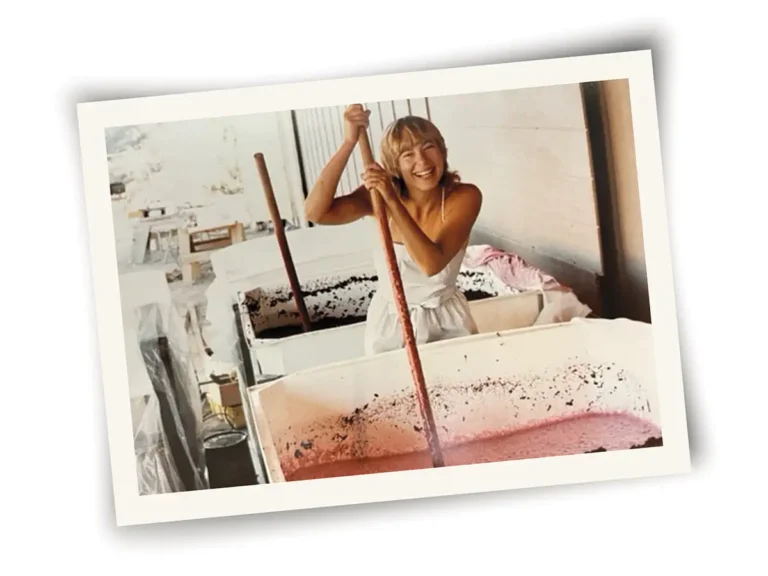

Boiling Away the Water

There are several ways to boil away the water but Steve recommended the crock-pot. The oven and stove are faster but the salt hardens to the pan and becomes difficult to scrape off. Outdoor evaporation takes much longer and flying insects land in the brine. It was raining when I arrived home, so I took Steve’s advice. It took five hours to simmer away two of my first 10 cups of water. Every few hours I scraped down the salt that had formed on the sides. At 20 hours I had a milky solution beginning to form crystals.

Crystal Size

Steve and I have been trying to figure out how to control crystal size. Fine crystals dissolve quickly into the food, but larger crystals are a nice finishing touch for a steak or salad.

If I stir the slushy salt water in a skillet and simmer away the water, I get a fine salt. The key to larger crystals is slow cooling and evaporation with no agitation, so using my food dehydrator gives me larger crystals.

Yield and Cost

I extracted about nine tablespoons of salt—a little less than one tablespoon from each cup of ocean water. Dave, my engineer husband, figured out that simmering the brine for 20 hours in a 150-watt crock-pot brought the energy cost to about $1 for a little over a half cup of salt. Steve, Dave and I agreed that our production cost was a bit high since a whole pound of kosher salt (about eight cups) costs between $3 and $5.

Evaporating the water in a sunny, windy location would be a more cost effective. That is how they make salt on the Hanapepe beach in Kauai, where families have been farming sea salt for generations.

Red Oak Smoked Salt

It turns out Steve also builds mobile wood-fired ovens with his brother Mike. So Steve suggested we try boiling off the water more rapidly in a pan on the 700° hearth of his brother’s oven. Mike parks his California Wood-Fired Catering oven at Corner Coffee House and Deli in Los Olivos on weekends and sells pizzas to virtually everyone who comes within range of the rich fragrance of wood-baked pizza drifting through town.

When we arrived, people were lined up for pizzas. It was lunchtime and we agreed that chanterelle and arugula pizzas would help us wait more patiently for oven space to open up. When we put our stainless skillet containing the salt-water slush onto the hearth, it only took a few minutes for a crust of salt crystals to form and the water to evaporate. As an added bonus, the cooled crystals had a smoked red oak flavor accent, and the crystals were larger than those stirred dry on the stovetop.

Conclusion

Collecting ocean water for salt for individual use is not cost effective, and it’s a lot of work. To make it commercially viable would require a larger scale collection and evaporation process plus a costly safety analysis.

Did we take the risk and taste it? Yes. It was delicious—smoky with hints of palm, eucalyptus and lemon.

I suspect that if anyone can find the path to turn this into a sustainable cost-effective commercial product, it will be Steve. Ocean Pearl Sea Salt on our local grocery shelves? Watch for it.