Gettin’ Down with Papaya Man

Damien Raquinio Brings Aloha to Santa Barbara

[Photography by Erin Feinblatt]

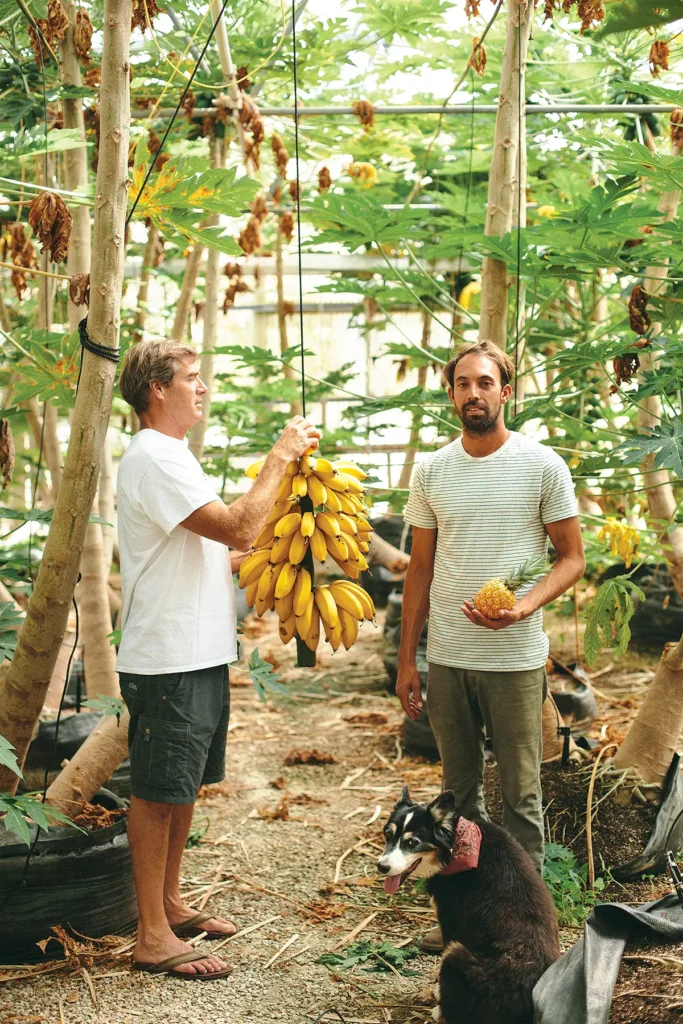

It’s a busy June-gloom day at the Saturday Santa Barbara Farmers Market. Musicians are strumming and singing. The sweet smell of summer fruit fragrances the air. And Hawaiian native Damien “Papaya Man” Raquinio is tending his cornucopia of homegrown papayas with the help of Soleil (a sweet waif of a spirit who greets me with a warm hug) and Logan Van Der Kar, who hails from Carpinteria avocado farming roots.

A pretty young lady strolls up to the Golden State Papaya booth and asks, “Are these grown here?” The team tells her yes, in Goleta. “And do they look like papaya trees?” she innocently adds.

The helpers politely answer again in the affirmative, before weighing and selling the sweet golden nectar of the gods to the satisfied customer, as well as to other fans, including chefs from Mesa Verde, Scarlett Begonia, Sama Sama Kitchen and other dining venues that support the farm stand. Then there are the rest of us who have discovered and crave the only papayas commercially grown on the mainland west of the Mississippi.

Growing papayas commercially outside of Hawaii and Florida has its challenges. Yet, they’ve found a “sweet spot” in The Goodland of Goleta.

Today there are two varieties of the Hawaiian fruit for sale: the smaller, sweet Sunset and a larger variety, Exotica, that the tall, reed-thin grower says sometimes has “hints of coconut” flavor. The 38-year-old farmer is feeling a bit peaked after attending the late-night Summer Round Up concert the night before at the Santa Barbara Bowl. But Damien promises to show me his exotic fruit farm—which he calls his “food forest” in Goleta’s More Mesa neighborhood—later, after the market closes and he packs up.

Damien grew up in Kona, Hawaii—his mother a pastry chef and dad a sunglasses sales rep on the sunny isle. He was raised on “hippie home lunches”—typically rice cracker with peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. Later, he discovered his love of plants while attending West Hawaii Explorations Academy—a science-based high school that offered classes in permaculture, hydroponics, fish farming/aquaponics and other earth sciences—in the mid-1990s.

“I chose to study hydroponics and learned that I loved plants. I always grew plants and had a garden as a kid and found the science of growing in water new and exciting!” he recalled.

There were lots of discussions and debates about hydroponic vs. organic gardening, a switch that Damien would make many years later. Damien moved to Santa Barbara in 1999—because his surf buddies attending SBCC told him there were a lot of girls here—and he labored in the toxic world of surfboard shaping and repair in what is now the more gentrified Funk Zone.

Fast-forward to 2013 and the transplanted Hawaiian surfer’s Whole Foods epiphany.

“I walked into Whole Foods and was amazed by the produce and fresh fruit section. Then I saw Hawaiian papayas for $7 a pound. We were used to getting them for FREE! I paid $12 for one papaya, and I was, like, ‘holy shit!’” he laughed.

An idea was born—and he partnered with equally passionate Adam Rhodes to start their tropical fruit growing business, which began in a greenhouse out at The Orchid in the far end of Goleta. Adam is a real estate developer and surfer who turned on to permaculture. They connected in the surf world, and both wanted to “reinvent themselves.”

“We were the first people crazy enough to try this!” Adam said.

“Papayas are 80 cents a pound in Hawaii,” he noted. “While waiting for our first crop to grow and become productive, we grew row crops of veggies, and we were happy with the results. Then we explored farmers markets three years ago.”

They grew their first papayas from non-GMO seeds from Hawaii—and were blessed with good trees.

“Then Old Man Winter Rainstorm flooded our greenhouse! If we didn’t get into a functional greenhouse, our crazy experiment would never fly,” said Adam. So they moved their growing operation to Island View Nursery in Carpinteria and to more affordable Goleta.

The two both admit it’s been a long road of trial and error—with many failures along the way.

“Every time we move, there are new issues. Both the climate and soil are different. It’s a nightmare!” says Damien, who takes failure in his stride.

“I’ve failed my whole life in normal systems,” he admitted, “I am dyslexic, and I am not scared of failure. It can be a learning experience.”

Once they made it to the farmers markets, the feedback was so positive (even though they were nowhere close to being ready with small yields and needed more volume to make the experiment economically feasible) that they forged ahead.

“Most Hawaiian papayas are GMO and picked hard and green. Mexican papayas are picked hard and green and have little flavor and are sprayed with pesticides or irradiated for 20 minutes. We grow organically and pick ours the day before we sell them. That’s why they taste so good,” said Adam. “Taste good” is an understatement.

There are also four key elements, according to the farmers: good genetics, good soil, the right environment and the right amount of light.

Later, after he packed up for the day, I met Damien in Goleta so he could lead me to the spot I’d “never find in a million years.” I followed him in his blue Ford truck along a windy and hole-pocked dirt road. We passed rows of old, abandoned glass-paneled greenhouses with missing panes and graffiti decorating the exterior. We arrived at his two-acre greenhouse—with a table covered by a bright umbrella (the color of papayas) out front.

Inside was a steamy, jungly, Jurassic Park-like “food forest.” It brimmed with healthy papaya trees pregnant with fruit, towering banana trees with humongous deep green leaves as wide as elephant ears, twisty tomato plants, dark green vines of wonderful purple Hawaiian sweet potatoes, along with turmeric, passion fruit and dragon fruit (pitaya) in the works.

Raquinio realized he wanted to take the permaculture system to a commercial level and create a food forest where plants and companion plants work together.

“These are epic greenhouses that I am dialing in!” Damien said enthusiastically in his surf lingo, as he described his process of soil-grown greenhouse tomatoes, papayas and other fruits being produced, using natural and organic methods. (Some of his growing methods he prefers to keep secret, including a special fertilization technique.) In addition to the two-acre greenhouse, the partners are growing on two acres of adjacent leased outdoor land.

“Aren’t they cute?” he says about a stunning row of papaya trees. What guy uses the word “cute,” I wonder? A cute one, it seems, who also uses a skateboard or scooter to get around while tending his produce.

Even songbirds find comfort in this tropical growing paradise—singing light-hearted songs that seemingly

add sweetness to the fruit. I even had a chance to smell the heavenly sweet papaya flower on the trees.

Growing papayas commercially outside of Hawaii and Florida has its challenges. Yet, they’ve found a “sweet spot” in The Goodland of Goleta, when the sun shone upon the seemingly magic growing pocket even on this foggy June-gloom day. The proof is in the produce: deliciously sweet papayas, tasty Japanese Pink winter tomatoes and other varieties; five types of bananas and three of pineapples. Who knows what else will emerge from the experimentation with seeds from Brazil and Hawaii that this dynamic duo are pursuing?

Perhaps the most stealth product is the Okinawan purple sweet potato (Hawaiian name is Uala). I prepared these delectable and pretty root vegetables with coconut milk for Thanksgiving dinner last year, and they were the hit of the dinner table.

“It’s an ongoing giant experiment! Plants are funny. They respond positively and negatively to everything you do to them,” Damien said. Kind of like people, I thought to myself, noting that many of Damien’s aphorisms about plants also apply to humans.

“Do your plants speak to you?” I asked. Not surprisingly, he answered, “They do!”

The future?

“We hope to have mangos in one to two years,” said Damien as he showed me the small, pretty green 1-month-old plants he started from seed—rootstock that he will graft.

“Sometimes I have to re-learn everything I thought I knew. One door opens to a whole lot of other questions! Sometimes it takes me way left field—that’s a good thing!”

There’s only so much you can do watching a papaya grow—which, like a baby, takes nine months from seed to maturity.

“Most of my day consists of fixing problems and taking care of odds and ends—which is insane! All day, every day, and it’s not fun,” he lamented. “There’s irrigation, infrastructure and management,” in addition to growing and doing things he’s never done before.

Then, on a brighter note, he tells me “We’re still growing and learning. Next year I expect sales to be amazing. It’s a great product, and everybody loves it. Farming is cool.”

And with that, he takes off down the pathway on his skateboard to fix a leak.