Acorn Eating: A Santa Barbara Tradition

Did you know that acorns provided about 20% of the rural diet in Italy and Spain as recently as the 19th century? Acorn consumption was also widespread in Santa Barbara County before Europeans arrived. The oak nuts were a staple of native diet in much of California as early as 3,500 years ago.

At Spanish contact, 300,000 native Californians were harvesting more than 60,000 tons of acorns a year—more than today’s sweet corn harvest. Acorns formed as much as half of the diets of many inland Native American groups and were a vital component in the Chumash diet.

One shouldn’t be surprised: Acorns are nutritious, easily stored and make superb bread meal. An ideal food, one would think. Unfortunately they take a great deal of preparation to remove bitter-tasting tannic acid, which has to be leached away with time-consuming care before consumption. Hardly surprisingly, balanophagy is alive and well in California.

What is Balanophagy?

The word even defeated my faithful Shorter Oxford Dictionary. I turned to the full-length version, and was stumped again. The ultimate arbiter of the English language had never heard of the word. But I managed to glean enough information from a Latin dictionary to establish that balanophagy is acorn eating. Then I went to the Web, typed the word out of curiosity into Google and was astounded to find dozens of entries on this seemingly obscure subject. Acorn eating is a serious field of study and favorite part of the diet for more than a few people, archaeologists among them, many of them working in California.

The Edible Landscape

California is a vast network of edible landscapes. Late spring and early summer was a special time, when fresh greens abounded and people could feast off miner’s lettuce, the unrolled fronds of bracken ferns, wild pea leaves and many more wild vegetables. Next, wild flowers burst into vibrant color, then into seed for the all-important grass harvest. By late summer and during early fall, blue elderberries, manzanita berries and other fruit reached perfection. Fall was the time of the nut harvests—hazel, piñons and, above all, oak acorns.

Fifteen species of oak grow from Southern California to Oregon, most of which provide a good harvest every two or three years, the yield varying greatly from one grove to the next. Acorns are not only plentiful, but have excellent nutritional value. Once processed into meal before cooking, they have between 4.5% and 18% fat, as high as 70% carbohydrates and about 5% protein, the proportions varying with the species. Compare this food value with maize and wheat, which contain about 1.5% fat, 10.3% protein and 73% carbohydrate.

Add to these stellar nutritional qualities a tolerance for storage, and acorns are an ideal food. Some groups stored acorns for up to two years, to compensate for oak crop fluctuations. They kept them in baskets inside their houses or in large, raised outdoor granaries, carefully insulated against moisture and protected against rodents.

Unfortunately, oak acorns are a labor-intensive crop, which accounts for the decline in balanophagy today. The work began with the harvest. These were the two or three busiest weeks of the Indian year. As with grass seeds, the harvest required exquisite timing, reaching the trees before the acorns fell off into the mouths of waiting deer feeding on the nut-rich mast as it rotted on the ground.

At harvest time, entire families would camp close to the oaks, the men taking advantage of the rich acorn droppings to hunt deer feasting under the oaks. The yield from a single tree could be as high as 55 pounds or more. But the harvest was easy compared to the necessary processing to make the nuts suitable for consumption. This was when the women’s hard work began.

How Acorns Were Processed

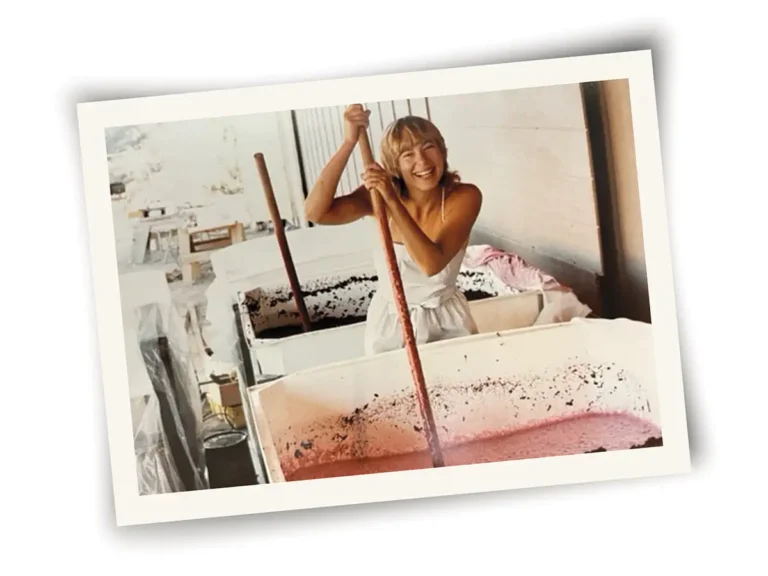

Before the days of food processors, turning shelled nuts into meal took hours of careful pounding, far longer than milling grass seeds. First the women cracked the shells with a hammer stone, then inspected and winnowed them, and finally crushed them into meal with carefully shaped stone pestles and mortars. Once it was pounded to a fine consistency, they sifted the flour through a tightly woven basket, and it was finally ready for leaching. We have few estimates as to how long this lengthy process took. UCLA anthropologist Walter Goldschmidt once observed a woman grind up six pounds of dry shelled acorns in three hours.

Even then, the meal was inedible until leached of its acids. You can leach acorns in various simple ways. The simplest, and perhaps the earliest, Native American method required immersing them in water or mud for weeks, even months, before pulverizing. This technique sweetened the acorns, but removed only a fraction of the tannins and involved a high spoilage rate. Soaking was an inefficient method, which did not produce enough treated acorns to support a large number of people. It also required ample water, so people located their base camps close to streams.

Once acorns became a staple in their own right, many groups switched to a more labor-intensive processing system. Once pounded, the women spread the meal in a porous depression in the ground. Leaching took between two and six hours, carried out by flushing water repeatedly through the meal into the soil below.

This long, tedious process consumed enormous amounts of time. For example, Goldschmidt’s six pounds of pounded acorns became 5.3 pounds of meal. Leaching this sample took just under four hours, about 1 3⁄4 hours per two pounds. Even today’s cooks, with all their sophisticated technology, still leach acorns by soaking them in repeated batches of hot or cold water.

Once leached, acorn meal made excellent bread and a variety of soups and gruels. Acorn bread is sweet and very nice to the taste, but you will probably have to make your own. I have not seen it on store shelves.

The Chumash living inland, away from the rich fisheries of the Santa Barbara Channel, relied heavily on acorns. They also traded nuts or processed meal to people living on the coast. For centuries, canoe loads of acorns crossed the Santa Barbara Channel, where the skippers bartered them for much-valued shell beads, manufactured on Santa Cruz Island. In the centuries before Europeans arrived, shell beads became a form of currency that traveled as far inland as the Sierra and even into the Southwest.

Today, we’ve almost forgotten about the nourishing acorn, which almost never figures in most peoples’ diet. More’s the pity, for this important ancient California food once sustained thousands of people in Santa Barbara County and elsewhere, through drought and years of plenty. Acorns were a staff of life for native Californians. Fortunately, both Chumash and other cooks have preserved some of the elements of a unique cuisine from the distant past.

Want to Try Processing Acorns? Click here for instructions on processing acorns using a cold water or a hot water technique.