The Lowdown on Loquats

I first encountered loquats when I moved to Santa Barbara. They seemed to lurk everywhere as a tall shrub with leathery evergreen leaves, an underappreciated feature in the landscape. When I first tried the fruit, I was put off by its large, numerous seeds and the fuzz on the skin. But upon closer inspection, the juicy flesh revealed flavors of apricot, mango, pear and cherry. I was intrigued. What else could this unassuming plant have to offer?

Loquats in Horticulture and Botany

The loquat, or Eriobotrya japonica, belongs to the Rosaceae, or rose family, alongside many other commercially important fruits in the apple subtribe such as apples, quince, medlar, pear and our native toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia). This evergreen shrub or small tree can grow up to 30 feet tall and spread 15 to 30 feet wide. Thriving in sunny locations and tolerant of a wide range of soil conditions, it makes an excellent background shrub in the garden. In fall and early winter, creamy white fragrant flowers appear. Many parts of the plant, including the undersides of its leaves, flower buds and fruits, are covered in rusty brown hairs.

The genus Eriobotrya derives from the Greek erion (wool) and botrys (cluster of grapes), referring to the tomentose yellow-orange fruits that grow in clusters. Loquat fruits resemble a small pear-shaped juicy apricot containing three to seven large seeds and ripen 90 days after flowering. The fruits must ripen on the tree, and are fragile once picked, limiting their potential as a commercial fruit crop. When harvesting loquats, look for fruits that are dark in color and slightly soft but not wrinkled. Some consumers prefer to peel off the fuzzy skin before eating.

Loquat History and Cultivation

Eriobotrya japonica is native to south-central China but has been cultivated in Japan for over 1,000 years where it was first thought to have originated. In China, loquats are called pipa; in Korea, bipa; and in Japan, biwa. Interestingly, all three countries have loquat-shaped lute musical instruments that share the same corresponding name.

The global distribution of loquats began when they were introduced to Paris in 1784 and London in 1787, before spreading to the rest of the Mediterranean region. Between 1867 and 1870, loquats were introduced to California from Japan and to Florida from Europe.

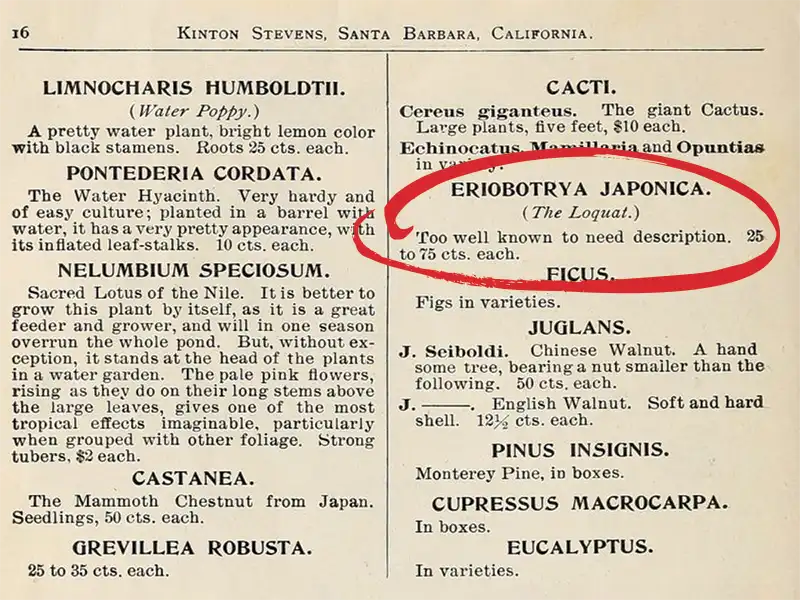

By the 1870s loquats were commonly cultivated in California, as an ornamental plant. Climates farther south, from Santa Barbara to San Diego, proved superior for fruit production and loquats became a common feature in mission gardens. Ralph Kinton Stevens, the first owner of Tanglewood—the property that would later become Madame Ganna Walska’s Lotusland—included Eriobotrya japonica in his 1891 nursery catalog, noting that it was “too well known to need description.” Prices ranged from 25 to 75 cents each.

Charles P. Taft, a fruit grower who settled in Orange County in 1883, took it upon himself to improve commercial loquat varieties. After raising 50 plants from seed, he introduced his first selection, ‘Advance,’ in 1897. In the years that followed, he amassed a collection of over 1,500 loquat trees on his property and introduced other cultivars to the trade, including the still-popular ‘Champagne’ in 1908.

Many cultivars have been selected for fruit color, flavor, shape and a higher fruit-to-seed ratio. The “Chinese group” tends to produce large, deep orange, pear-shaped fruits, while the “Japanese group” bears smaller, lighter-colored fruits. White-fleshed varieties are generally better suited to cool coastal areas.

Loquat Uses

After harvesting (March–June), loquat fruits can be stored in the refrigerator for one to two weeks. One of the more common ways to process loquat fruits is by making jams and jellies. Due to their high pectin content, no additional pectin is needed for the preserves to set. Loquat salsas and chutneys are also popular, and the fruits can be baked into cakes, crumbles and cobblers.

Loquat leaves can be made into a tea after the fuzzy hairs on the undersides are removed. In Japan, loquat leaf infusions, or biwa-cha, are traditionally used to treat coughs, stomach issues and kidney ailments. Warm compresses made from the leaves are also used to relieve arthritis and joint pain.

In Italy, the seeds are used to make an aromatic liqueur similar to amaretto (made from stone fruit kernels and seeds) and nocino (made from unripe walnuts). Like other stone fruits, loquat seeds contain cyanogenic glycosides that break down to release hydrogen cyanide in the body. Great care should be taken when consuming seeds or seed extracts.

Last spring, I attended a dye class in Japan where I dyed a silk bag with a background of loquat dye extracted from crushed leaves and branches. Loquat leaves are high in tannins, similar to tea leaves, and have a tendency to adhere to natural fibers. When soaked in warm water for several days and repeatedly brought to a boil, loquat leaves yield a delightful pink-orange color that can be used to dye both animal and plant fibers.

The next time you are walking around Santa Barbara in the spring, try to find loquat trees. They are quietly growing in unexpected places—ripe for foraging. This often ignored and undemanding fruit tree has so much to offer, not only for its pure ornamental value, but for the edible and creative products it inspires.

How to Eat a Loquat

When selecting a ripe loquat, pick ones with the darkest yellow color, almost glowing. The kind that if you don’t eat today will be taken by the birds tomorrow. Similar to an apple or pear, the fruit of the loquat is an enlarged fleshy structure called a hypanthium.

Hold the loquat fruit with the stalk (pedicel) resting in your fingertips. Starting at the top, carefully peel away the skin, like a banana. If your fingers can’t do it, use a paring knife to get the peel started.

The small sunken disc remaining at the top of the fruit is where the other floral parts were attached to the hypanthium. It can be removed with a paring knife or fingers and should come out in one piece.

Shallowly cut the loquat in half lengthwise with the paring knife, then pull it apart to reveal the large seeds. The seeds will easily fall out of the fruit. These seeds can be dried and used to make nespolino, if you like—an infused liqueur similar to amaretto or nocino.

At this point, you can gently pull away the soft fibers (pericarp) that had surrounded the seeds, or leave them, as they have no effect on the taste or texture. You now have two juicy bites of fresh, sweet loquat to enjoy. These can go into fruit salads, or be made into jam, but please take some simple bites just as they are.